The case of Elsa Plotz

Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz

THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS

« Une réplique, appropriée par Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), d’un original présenté à la Société des artistes indépendants de New York en avril 1917.»

Could this be Fountain’s new museum label?

« Raconte ce détail à la famille : les indépendants sont ouverts ici avec gros succès. Une de mes amies sous un pseudonyme masculin, Richard Mutt, avait envoyé une pissotière en porcelaine comme sculpture. Ce n’était pas du tout indécent, aucune raison pour la refuser. Le comité a décidé de refuser d’exposer cette chose. J’ai donné ma démission et c’est un potin qui aura sa valeur dans New York. J’avais envie de faire une exposition spéciale des refusés aux Indépendants. Mais ce serait un pléonasme ! Et la pissotière aurait été « lonely ». à bientôt affect. Marcel »

— Duchamp’s letter to her sister Suzanne Duchamp (April 11, 1917).

How come that “the most influential piece of modern art”, a public men’s urinal signed R. Mutt, apparently sent by some Richard Mutt to the great inaugural show of modern art in America, opened in New York City on the evening of April 10 of 1917, has been rejected and disappeared before any chance of being exposed to any public audience?

Fountain’s authorship is a mystery, probably a calculated one by Marcel Duchamp himself. No one knows for sure. Writers and scholars claim, since 2002, that the famous virtual artwork was a ‘readymade’ by Elsa Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven, attributed to Duchamp by André Breton in 1935. Duchamp finally assumed the Fountain’s authorship in 1950, thirty-three years after its submission to the “First Annual Exhibition of The Society of Independent Artists in 1917.

The so-called Fountain is a non-existent artwork — a virtual entity and a purely conceptual object that has defined contemporary art for almost a century.

Duchamp’s commercial replicas of a similar urinal under the title “Fountain” are indeed copies, iterations, of the original ‘object’ sent to the New York exhibition by someone under the pseudonymous R. Mutt. Above all, the Fountain is the title of a printed picture from a photographic composite image by Alfred Stieglitz specially made for the avantgarde magazine issue n.2 of The Blind Eye (May 1917). So what we have from the year of the exhibition is an image printed on a magazine of an art object (a ‘readymade’) and a title: Fountain. This title and the corresponding picture of the lost thing is the ‘ekphrasis’ of one of the most robust paradigms of twenty-century art. Who made this object? Who found (or ordered) this ‘readymade’? As dictated by André Breton in 1935, eighteen years after the obscure event of its presentation and disappearance, was Marcel Duchamp. But no, or at least not him alone. Alfred Stieglitz did a composite picture of the rejected men’s urinal for The Blind Man — a Dada publication conceived by Duchamp, Henry-Pierre Roché and Beatrice Wood, who became its publisher. Last but not least, R. Mutt’s signature on the top-right border of the urinal suggests that it was Elsa Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven who signed the artwork and, most probably, the one who ordered and sent the ‘sculpture’ to the great exhibition of the Independents (1). Eight years after her death (1927), Fountain became the most famous readymade.

If this is true, multiple shadows would permanently taint Duchamp’s originality.

A compilation of the most relevant writings proving and disproving Duchamp’s authorship of the Fountain follows, plus a link to Elsa Plotz’s poetry anthology.

This post derives from a recent discussion with my friend and artist Natalia de Mello, whom I vividly thank.

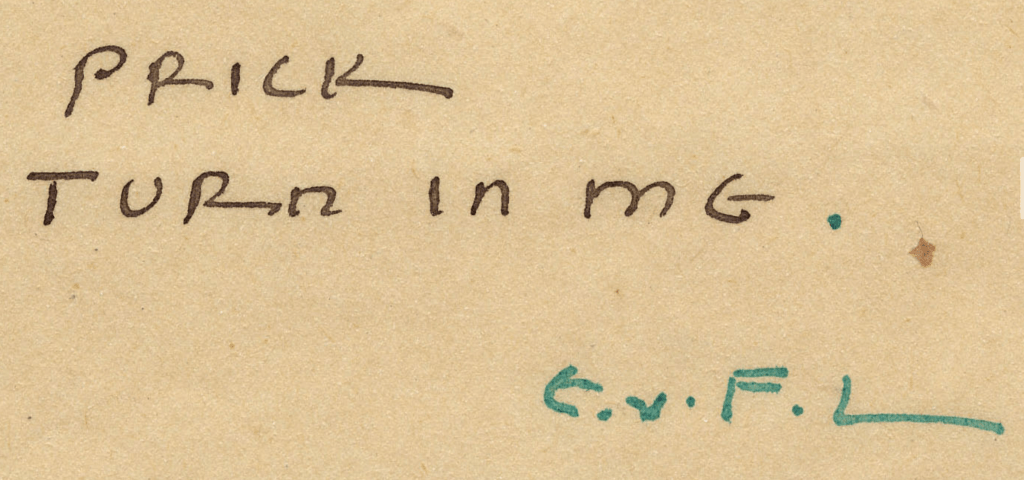

1—The Rs in Elsa’s handwriting don’t fit R. Mutt’s signature.

A C-P

Brussels, Mon 5, Jun 2023.

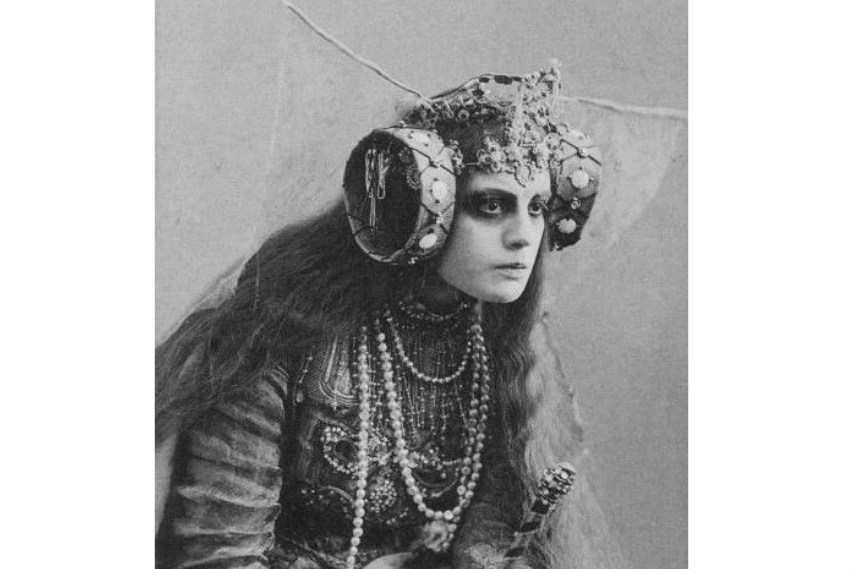

Photographer unknown (probably before 1923)

Elsa Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven (born Else Hildegard Plötz; (12 July 1874 – 14 December 1927) was a German-born avant-garde visual artist and poet, who was active in Greenwich Village, New York, from 1913 to 1923, where her radical self-displays came to embody a living Dada. She was considered one of the most controversial and radical women artists of the era — Wikipedia.

Seeing in the dark

Below is a compilation of relevant texts published on the controversial relationship between Elsa Plötz and Marcel Duchamp.

(2002)

¶¶¶

“Limbswishing Dada in New York Baroness Elsa’s Gender Performance”

Irene Gammel

With me posing [is] art—aggressive—virile—extraordinary—invigorating—antestereotyped—no wonder blockheads by nature degeneration dislike it—feel peeved—it underscores unreceptiveness like jazz does.

The Baroness to Peggy Guggenheim, 1927Felix Paul Greve […] hat intellektuellen Ehrgeiz—Aber er will ‘Originalitat’—von der ist er strikter Antipod. Ich bin das—was er nicht ist. So musste er mich hassen—lassen.

The Baroness, “Seelisch-chemischebetrachtung”1

Celebrating her posing as virile and aggressive art in the first epigraph, the Data artist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, nee Plotz (1874-1927) summed up her remarkable life and work just months before her mysterious death in Paris. Known as the Baroness amongst the international avant-garde in New York and Paris of the teens and twenties, the German-born performance artist, model, sculptor, and poet was a party to the general rejection of sexual Victorianism, launched with the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, the so-called Armory Show, in Manhattan. Before coming to New York, the Baroness had undergone a picaresque apprenticeship amongst the Kunstgeiuerbler avant-garde in Munich and Berlin from around 1896 to 1911, before following her long-time spouse Felix Paul Greve (aka F.P. Grove) on a quixotic immigration adventure to Kentucky. After Grove’s desertion, she made her way to New York and promptly married the impe-cunious (but sexually satisfying) Baron Leopold von Freytag-Loringhoven. Soon a tided war widow (the Baron was incarcerated by the French in 1914 and committed suicide in 1919), the Baroness claimed her new spiritual home amidst an energetic and international group of vanguard artists– many of them exiles from Europe. From 1913 on, she threw herself with abandon into New York’s experimental ferment, quickly becoming the movement’s most radical and controversial exponent.2

(…)

Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée CRCL JANUARY-MARCH 2002 MARS-JUIN

0319-051X/2002/29.1/1 © Canadian Comparative Literature Association

https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/crcl/index.php/crcl/issue/view/671

¶¶¶

The Mama of Dada

By Holland Cotter

NYT, May 19, 2002

The Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927) — known to her amused, admiring, often quailing friends simply as the Baroness — was a public event, a proto-Happening. She painted her shaved head red. She wore a tomato-can bra, a bustle with a taillight and a bird cage around her neck with live canaries inside. The streets of New York were her theater. Dada was the name of her act.

Many people who watched her clanking imperiously through Greenwich Village in the years just after World War I probably took her for only another New York nut job; until recently, history has done that too. But she was also an artist, a poet, a voluble fixture of the cultural avant-garde and a guerrilla fighter in sexual politics. This is how she comes across in Irene Gammel’s ‘‘Baroness Elsa,’’ the first full account of the Baroness’s life. It attempts, on the whole persuasively, to position her as a catalytic figure in the American art of her day and in the evolution of certain more contemporary forms — junk art, performance art, body art.

…

Elsa came into her own as part of the New York Dada scene. Her sexual fieldwork continued, with many successes and a few notable disappointments. She developed a crush on Marcel Duchamp, who responded with passive evasion. (‘‘Marcel, Marcel, I love you like hell, Marcel’’ was her cri de coeur.)

(…)

She started to make art: painted portraits, witty, delicate sculptures of found materials and assemblage-style costumes. Her beyond-the-fringe daring was a power of example for her male colleagues — the wannabe Dadaist Ezra Pound spoke approvingly of her ‘‘principle of nonacquiescence’’ — and may have produced collaborative results. Ms. Gammel presents strong evidence that the Baroness supplied Duchamp with the urinal from which his groundbreaking ‘‘Fountain’’ was made, and provided the prototype for his cross-dressed Rrose Selavy.

¶¶¶

Baroness Elsa

Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity-A Cultural Biography

Irene Gammel

MIT Press, 2002

The first biography of the enigmatic dadaist known as the Baroness–Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927) is considered by many to be the first American dadaist as well as the mother of dada. An innovator in poetic form and an early creator of junk sculpture, the Baroness was best known for her sexually charged, often controversial performances. Some thought her merely crazed, others thought her a genius. The editor Margaret Anderson called her perhaps the only figure of our generation who deserves the epithet extraordinary. Yet despite her great notoriety and influence, until recently her story and work have been little known outside the circle of modernist scholars.

In Baroness Elsa , Irene Gammel traces the extraordinary life and work of this daring woman, viewing her in the context of female dada and the historical battles fought by women in the early twentieth century. Striding through the streets of Berlin, Munich, New York, and Paris wearing such adornments as a tomato-soup can bra, teaspoon earrings, and black lipstick, the Baroness erased the boundaries between life and art, between the everyday and the outrageous, between the creative and the dangerous. Her art objects were precursors to dada objects of the teens and twenties, her sound and visual poetry were far more daring than those of the male modernists of her time, and her performances prefigured feminist body art and performance art by nearly half a century.

https://www.standaardboekhandel.be/p/baroness-elsa-9780262572156?utm_source=pocket_saves

¶¶¶

“My Heart Belongs To Dada”

By René Steinke

Aug. 18, 2002

The New York Times Magazine

(…)

She had a tall, lithe frame, ‘‘very Gothic,’’ and ‘‘a wonderful gait,’’ according to the photographer Berenice Abbott. Her fierce, strange beauty and her predilection for taking off her clothes made her a favorite model for artists like Robert Henri, William Glackens and Man Ray. But even before coming to New York, as she spent her youth chasing an ambition to become a ‘‘real free true lady artist,’’ the Baroness played the part of model and muse. As a young runaway in Berlin, she posed as a living statue at the Wintergarten Theater, in a kind of live pornography show disguised as edifying classical art.

(…)

If Duchamp was right about the Baroness being the future, her time may now have arrived. The Francis M. Naumann Fine Art gallery recently devoted an exhibition to her, and a new biography (‘‘Baroness Elsa,’’ by Irene Gammel) finally establishes her rightful place as the first American performance artist. Now that it is practically impossible not to wear mass-produced clothing, encouraging women to hire stylists to make themselves look different, there is enormous appeal in the Baroness’s surreal ensembles.

(…)

The opposite of the passive model, the Baroness was Duchamp’s ‘‘Nude Descending a Staircase’’ come to life and strolling out the door. In 1921, she starred in a film made by Duchamp and Man Ray, titled ‘‘Elsa, Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven, Shaving Her Pubic Hair.’’ In the two frames that remain (Man Ray accidentally destroyed the film during development), she appears to be dancing, spectacularly naked, after the barber has done his work.

¶¶¶

“Baroness Elsa and the Aesthetics of Empathy A Mystery and a Speculation”

Richard Cavell

On April 1st, 1921, the Socieété Anonyme of New York, which was the first American society devoted to the presentation of modern art, held a session on Dada which was immortalized in a drawing by Richard Boix (figure 5). In this draining we find a number of key figures within New York Dada, including Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp, all of whom are clearly identified by name. In the centre of the image, however, there is a figure resting on a pillar identified only as “La Femme,” and it is around this figure that a mystery has grown up (figure 6). The New York Dada scholar Francis Naumann has suggested an identification with a sculpture by Archipenko (figure 7), while admitting that “no specific sculpture by Archipenko—nor, for that matter, any other artist from this period—exhibits the unusual details that can be found in this illustrator’s flight of fancy” (“New York Dada” 14). Identifying the figure with Eve through the icon of the apple, Naumann notes contrariwise that from the “string attached to the woman’s elbow (or is it a beaklike extension of her nose?) a cup dangles freely in space, a detail that makes the sculpture look less like the depiction of a woman and more like an organ-grinder’s monkey ‘gone Dada’” (14). In the mystery of this figure Naumann sees the very reason why “people keep asking ‘what is Dada?’”

In the decade from 1986, when Rudolf Kuenzli published New York Dada, to 1996, when Francis Naumann issued “Making Mischief: Dada Invades New York”, the figure of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven has moved from the peripheries of New York Dada to occupy a central position, as the reproduction of her 1920 Portrait of Marcel Duchamp on the cover of Naumann’s book tellingly indicates (figure i). The reasons for this shift are many: one has to do with the increasing recognition of the historical importance of women in Dada (as in the anthology of articles recently edited by Naomi Sawelson-Gorse). Closely connected to this avenue of approach is that of feminist theory, which, by critiquing the notion of Dada as an exclusively masculinist activity, has opened up a space for important figures such as Elsa to emerge from obscurity. Another avenue along which Elsa studies have developed is that of sexuality: Elsa’s memoirs, published by Paul Hjartarson and Douglas Spettigue under the title Baroness Elsa, remain among the most breathtakingly frank documents of this period, and we are now beginning to understand that sexuality was absolutely central to Elsa’s art, be it her poetry, her prose or the artefacts she created. Finally, the growing interest in and research on Elsa’s German partner, Felix Paul Greve, has been accompanied by the realisation that their work constitutes much more of an intellectual 1

(…)

Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée CRCL JANUARY-MARCH 2002 MARS-JUIN

0319-051X/2002/29.1/1 © Canadian Comparative Literature Association

https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/crcl/index.php/crcl/issue/view/671

(2004)

¶¶¶

“Work of art that inspired a movement … a urinal”

Charlotte Higgins, arts correspondent

The Guardian, Thu 2 Dec 2004 12.12 GMT

A humble porcelain urinal – reclining on its side, and marked with a false signature – has been named the world’s most influential piece of modern art, knocking Picasso and Matisse from their traditional positions of supremacy.

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, created in 1917, has been interpreted in innumerable different ways, including as a reference to the female sexual parts.

However, what is clear is the direct link between Duchamp’s “readymade”, as the artist called it, and the conceptual art that dominates today – Tracey Emin’s Bed being a prime example.

According to art expert Simon Wilson, “the Duchampian notion that art can be made of anything has finally taken off. And not only about formal qualities, but about the ‘edginess’ of using a urinal and thus challenging bourgeois art.”

The Duchamp came out top in a survey of 500 artists, curators, critics and dealers commissioned by the sponsor of the Turner prize, Gordon’s. Different categories of respondents chose markedly different works, with artists in particular plumping overwhelmingly for Fountain.

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/dec/02/arts.artsnews1

(author and date unknown)

[2008]

¶¶¶

In Transition: Selected Poems [1923-1927]

by the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

https://digital.lib.umd.edu/transition/index.html

[2011]

¶¶¶

Body Sweats: The Uncensored Writings of Elsa Von Freytag-Loringhoven

by Elsa Von Freytag-Loringhoven

Mit Press (2011)

The first major collection of poetry written in English by the flabbergasting and flamboyant Baroness Elsa, “the first American Dada.”As a neurasthenic, kleptomaniac, man-chasing proto-punk poet and artist, the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven left in her wake a ripple that is becoming a rip–one hundred years after she exploded onto the New York art scene. As an agent provocateur within New York’s modernist revolution, “the first American Dada” not only dressed and behaved with purposeful outrageousness, but she set an example that went well beyond the eccentric divas of the twenty-first century, including her conceptual descendant, Lady Gaga.Her delirious verse flabbergasted New Yorkers as much as her flamboyant persona. As a poet, she was profane and playfully obscene, imagining a farting God, and transforming her contemporary Marcel Duchamp into M’ars (my arse). With its ragged edges and atonal rhythms, her poetry echoes the noise of the metropolis itself. Her love poetry muses graphically on ejaculation, orgasm, and oral sex. When she tired of existing words, she created new ones: “phalluspistol,” “spinsterlollipop,” “kissambushed.” The Baroness’s rebellious, highly sexed howls prefigured the Beats; her intensity and psychological complexity anticipates the poetic utterances of Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath.Published more than a century after her arrival in New York, Body Sweats is the first major collection of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s poems in English. The Baroness’s biographer Irene Gammel and coeditor Suzanne Zelazo have assembled 150 poems, most of them never before published. Many of the poems are themselves art objects, decorated in red and green ink, adorned with sketches and diagrams, presented with the same visceral immediacy they had when they were composed.

(2013)

¶¶¶

“The Hits of Lady Dada : Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven”

By Ben Robinson

Yuck ‘n Yum Winter 2013

Whether in art, politics, love or warfare, history is said to be written by the victors. The importance of Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 Fountain is surely beyond any doubt, having changed the entire art historical narrative irrevocably. In 2004, to no-one’s great surprise, it was voted the most influential artwork of the 20th century by 500 selected art world professionals. This article is not about to argue any different. But what if Fountain, that most influential artwork, was maybe the idea of someone else entirely, someone whose place in art history was largely forgotten and has only recently come to light?

In a 1917 letter from Duchamp to his sister Suzanne, he informed her that his submission to the Society of Independent Artists was in fact conceived by a friend:

“One of my female friends who had adopted the pseudonym Richard Mutt sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture; since there was nothing indecent about it, there was no reason to reject it.”

So could this mysterious friend have been Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and who was she anyway?

The Baroness was born in 1874 in Pomerania, Germany, and spent much of her early life as an actress and vaudeville performer. She had numerous affairs with artists in Berlin, Munich and Italy, studied art in Dachau, and married an architect in Berlin in 1901. This marriage became a ménage à trois with the poet and translator Felix Paul Greve, and in 1910 she emigrated to America with him. On moving to New York in 1913 she married the German Baron Leopold von Freytag-Loringhoven, got a job in a cigarette factory, and fell in with the city’s nascent Dada scene. Baron von Loringhoven hurried back to Germany at the outbreak of war, where he shot himself – an act which his wife characterised as the “bravest of his life”.

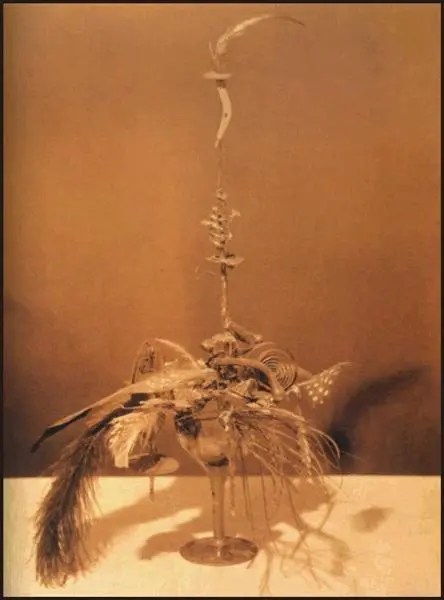

Freytag-Loringhoven cut an eccentric figure on the New York streets with her shaved head, black lipstick and riotous outfits of found-object ensembles, among them a tomato-can bra, a birdcage hat with live canary, and postage stamps pasted to her cheeks. She modeled for artists including Man Ray, and appeared in a short film by Ray and Duchamp titled The Baroness Shaves Her Pubic Hair. She wrote poetry that was published in the Little Review and inspired Ezra Pound, who wrote in his Cantos that the Baroness lived by a “principle of non-acquiescence.” While pursuing a thorough dismantling of the boundaries between art and everyday life, she created artworks whose existence has survived through many years of obscurity. The irreligious Dada object God is a 10½ inches high cast iron plumbing trap turned upside down and mounted on a wooden mitre box, a 1917 readymade that’s contemporaneous with Fountain and is now exhibited alongside it in the Arensberg Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

After her flowering with New York Dada, Freytag-Loringhoven was cut adrift when many of her fellow artists and poets returned home to Europe after the war. By the time she’d inherited enough money to travel to Paris in 1926, she was in declining health and dismayed by the many rejections of her English-language poetry in her resolutely Francophone new home. A disastrous stay in post-war Berlin came to nothing, though a return to Paris the following year seemed to promise some improved mental stability. However. she was to die alone of gas suffocation in her flat, either by suicide or fatal accident. She is buried at Paris’s Père Lachaise Cemetery.

The Baroness’s place in history might have been condemned to a mere footnote but for a sudden resurgence of interest in this unique Dada trailblazer. In 2003, Irene Gammel’s Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity told her extraordinary story in the context of feminist body art and performance art, while Body Sweats: The Uncensored Writings of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was listed by The New York Times as one of the notable art books of 2011. Even her unique and inflammatory fashions have appeared on the catwalks: for spring 2009, Maison Martin Margiela paraded models wearing a collection made entirely of refuse, and in winter 2009 Agatha Ruiz de la Prada took Elsa’s signature birdcage as the design cue for a skirt. The Baroness’s life and work had always defied specific categories, and she foresees junk art, performance art, body art, collage, found sculptures and assemblage by decades. It’s been a long time coming, but Baroness Elsa can finally claim a kind of victory.

https://www.yucknyum.org/zine/winter-2013/5/

God (1915)

(photo: Morton Schamberg)

¶¶¶

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

1874 — Świnoujście, Pologne | 1927 — Paris, France

Sculptrice et poétesse états-unienne.

À 18 ans, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven quitte sa famille pour s’installer à Berlin. Après deux mariages ratés, avec l’architecte August Endell en 1901, et avec l’écrivain Felix Paul Greve en 1907, elle s’installe à New York, où elle rencontre le baron Leopold von Freytag-Loringhoven, avec qui elle se marie en 1913. Dans les années 1920, elle devient alors célèbre à Greenwich Village pour ses accoutrements extravagants faits de vêtements artistiques farfelus (corbeille à papier ou seau à charbon en guise de chapeau) et ses comportements excentriques. Pour survivre, elle pose comme modèle pour différents artistes : Theresa Bernstein, George Biddle. Elle commence à faire ses premiers collages et assemblages, le plus souvent à partir d’objets trouvés (comme dans son portrait de Marcel Duchamp, photographié par Charles Sheeler). Elle aime fréquenter les salons avec le crâne rasé, en particulier chez les Arensberg, centre de l’avant-garde artistique et intellectuelle américaine. Nouvelle égérie du mouvement dada de New York, elle est surnommée Dada Baroness. Elle joue dans un film coréalisé par Marcel Duchamp et Man Ray intitulé La Baronne rase ses poils pubiens.

En 1915, elle réalise, avec Morton Schamberg, la sculpture God, formée par un tuyau de plomb sur un morceau de bois, que beaucoup considèrent comme l’expression parfaite du dadaïsme de New York. Dès 1917, elle publie de nombreux poèmes dans les revues littéraires avant-gardistes, Broom, The Liberator et The Little Review qui la consacre « première dada américaine ». Incapable de survivre à New York sans revenus fixes, elle retourne en Allemagne en 1923. En proie à des pulsions suicidaires, elle fait plusieurs séjours dans des hôpitaux psychiatriques. Elle meurt intoxiquée par le gaz dans son appartement parisien. Son autobiographie Baroness Elsa est parue en 1992, réalisée à partir de son manuscrit autobiographique et d’extraits de lettres.

Béatrix Pernelle

Extrait du Dictionnaire universel des créatrices

© 2013 Des femmes – Antoinette Fouque

https://awarewomenartists.com/artiste/elsa-von-freytag-loringhoven/

(2014)

¶¶¶

“How Duchamp stole the Urinal”

November 4, 2014 | By SRB

Scottish Review of Books

Calvin Tomkins met Marcel Duchamp in 1959 when he wrote an article about him for Newsweek. They were friends until the artist’s death in 1968. The Museum of Modern Art has just published a new and revised edition of Tomkins’ now standard 1996 biography of Duchamp. Ann Temkin, Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture at MoMA, praises Tomkins in her introduction for unfailingly bringing ‘a splendid lightness of touch to the weight of his careful and thorough research.’

Lightness is crucial to Tomkins’ assessment of Duchamp. He criticises those who take Duchamp too seriously. ‘Approach his work with a light heart’, Tomkins recommends, ‘and the rewards are everywhere in sight.’ This affable attitude, which demonstrated a warm friendship, has led Tomkins to brush aside all the recent research that undermines Duchamp’s own account of his life, which Tomkins used as the basis of his biography.

The startling fact has now emerged that Duchamp stole his most famous work, the urinal, from a female artist, robbed it of its original meaning, and turned it into something it was never intended to be: a piss take against the whole of art. This revelation undermines the whole argument of Tomkins’ book, discredits his ‘careful and thorough research’ and changes the history of art.

When the mood took him, Duchamp could be honest about his dishonesty. In an interview for Vogue in 1962, he told William Seitz ‘I insist every word I am telling you now is stupid and wrong.’ Research has now revealed that Duchamp’s account of his life is a hall of smoke and mirrors. But, extraordinarily, there is a ‘smoking gun’ in all this subterfuge, and Duchamp is holding the incriminating weapon himself.

On April 11, 1917, just two days after the directors of the Society of Independent Artists had rejected a urinal as a submission for their exhibition, Duchamp wrote to his sister telling her that ‘One of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture’. This letter did not enter the public domain until 1983. It contradicts Duchamp’s own later account of this seminal incident.

In The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (1979) Arturo Schwarz reports that Duchamp claimed that he and his friends Walter Arensberg and Joseph Stella went shopping on Fifth Avenue, ‘after a spirited conversation at lunch’, and bought a urinal from the J. L. Mott Iron Works. Duchamp then took it back to his studio, signed it R. MUTT, and submitted it to the Independents exhibition, calling it Fountain.

The board of the Society of Independents, of which Duchamp and Arensberg were members, had decided that they would hang every work of art submitted. Duchamp wasn’t present when the urinal, a late entry, was considered. Arensberg argued that it was art because an artist had chosen it. Mere choice, he claimed, could be transposed to an object and turn it into a work of art. The board, however, voted to reject the item on the grounds that it wasn’t art. Arensberg, and then Duchamp, resigned in protest.

The submission and rejection of Duchamp’s urinal is now regarded as one of the key, early turning points in the history of modern art, on a par with the revolutions of Fauvism and Cubism, De Stijl and Der Blaue Reiter. Fountain is always cited as the source of Conceptualism, the modern art movement that America, rather than Europe, gave the world. In Conceptual Art the idea behind the work is more important than its visual appearance or any aesthetic considerations.

Many leading Duchamp scholars, in particularly William Camfield, Rhonda Roland Shearer and Glyn Thompson, in research published between 1996 and 2008, have discovered that this account of the urinal’s submission is simply not true. Duchamp and his friends couldn’t have bought the urinal from the J. L. Mott Ironworks because they didn’t sell that particular model. And the urinal was submitted untitled. Thompson argues convincingly that it was Alfred Stieglitz who named it Fountain when he photographed the rejected entry later.

The public outrage has also been hugely exaggerated. Since the urinal was never exhibited, no one saw it. Arensberg tried to generate publicity through his modest magazine, Blind Man 2, but there was little interest. Guillaume Apollinaire referred to the incident in the Mercure de France fifteen months later but he dismissed it as a pale American imitation of the famous blague known as the Boronali Affair of 1910 in which some abstract paintings which fooled the critics were later shown to have been made by a donkey’s tail. Japes against modern art were common by this time. They’d begun much earlier in Paris, when in 1883 Alphonse Allais exhibited a sheet of white paper in a frame and called it Anaemic Young Girls at their First Communion in the Snow.

Tomkins ignores all these discoveries in his new edition. He argues that Duchamp wanted (for reasons he doesn’t explain) to keep his involvement in the ‘affair’ of the urinal secret. This was why he pretended in his letter to his sister that a ‘female friend’ had submitted the object. But this explanation makes no sense because his sister, a Red Cross nurse in Paris, had no contacts with the New York media and, anyway, Duchamp’s letter would have taken weeks to arrive in war-torn Europe, long after public interest in the incident had fizzled out. The most obvious explanation is that Duchamp in his letter was telling the truth. But if he was, who then was this ‘female friend’?

The great new addition to the story of Duchamp, besides all the excellent, forensic work by Duchamp scholars, is the research of Irene Gammel. Her enthralling, moving and beautifully paced biography, Baroness Elsa, published in 2002, not only throws a spotlight, for the first time, on a highly influential creative figure in the maelstrom of art at the turn of the century, but radically changes our perception of Duchamp.

Baroness Elsa was born plain Else Plotz in Swinemunde, Germany, in 1874. Her father was a builder and local councilor who philandered freely, beat her mother and, Elsa believed, inflicted her with syphilis. In her poem, Coachrider (c 1924), Elsa wrote:

Look at Papa – Killer!

He beams – lovably – virile – despotic by blood – I adore – abhor him –

Elsa’s mother, Ida, forbidden to play her beloved piano by her husband, retreated into religion and romantic fiction. She insisted that her two daughters pray before they went to sleep. ‘Like going for a pee before bed,’ their atheist father laughed back. Ida attempted suicide and later died in an institution in 1893. As Elsa put it, she ‘left me her heritage … to fight.’

Elsa’s genius was to find new ways to break out of the social straightjacket that bound women in the 19th Century. She turned her life into a theatrical performance in which she could fight her mother’s battles openly, in public, in the street, whenever and wherever she wanted to, not when any man told her she could. Djuna Barnes, a friend late in Elsa’s life, wrote ‘People were afraid of her because she was undismayed about the facts of life – any of them – all of them.’

Gammel unravels the complex threads of Elsa’s marriages, first to the Jugendstil architect August Endell, and then to Felix Paul Greve (later Frederick Philip Grove), the translator of Oscar Wilde, who with Elsa’s helped, faked his own suicide in 1909 to escape his creditors. This event brought her to America a year later.

Her third marriage, in 1913, was to Leopold Karl Friedrich Baron von Freytag- Loringhoven, the impoverished son of a German aristocrat who had, like Felix Greve, fled Europe to escape debts. Soon after the marriage, Leopold vanished with Elsa’s paltry savings. However, he left her with a title and an entrée into the most exclusive artistic circles in New York. The Armory Show had just transformed New York, making it modern and cosmopolitan. The Baroness was soon a habituée of the Arensberg circle, where Duchamp himself held court.

Duchamp’s relationship with Elsa came at a crucial time in both of their lives and merited re-examination in Tomkins’ new edition. But the Baroness is given the same half paragraph as before, once more entertainingly dismissed as a woman ‘unhampered by sanity’. Though Tomkins acknowledges her innovative use of found objects – she sewed ‘flattened tin cans, and other strange talismans’ on to her dress – he doesn’t take her interest in them seriously. Found objects could be works of art for men; for women they were merely decorative fetishes.

The Baroness and Duchamp had studios in the same Lincoln Arcade Building, on 1947 Broadway in1916. According to Elsa, they enjoyed many midnight rendezvous. Elsa’s nickname for Duchamp was m’ars. She loved puns. M’ars was a word play on my arse and Mars, the god of war. She called herself ‘m’ars teutonic’, a female god of war, with, of course, a magnificent German posterior.

The American painter, Louis Bouché, recounted a remarkable incident. He’d bought Elsa a newspaper clipping showing Duchamp’s painting Nude Descending a Staircase. He described the scene: ‘she was all joy, took the clipping and gave herself a rub down with it, missing no part of her anatomy’, while reciting her own poem ‘Marcel, Marcel, I Love You like Hell, Marcel.’

Tomkins just quotes the line but leaves out the context, giving the impression that Elsa was, like many women, besotted with his hero. But, as Gammel correctly observes, Elsa’s ‘engagement with Duchamp was astutely critical.’ The rub down was cleansing as well as erotic; she presumably used the newsprint not just to arouse herself but also to wipe her ‘ars teutonic’.

Nude Descending a Staircase was the painting that had made Duchamp famous in America when it was exhibited at the Armory Show in 1913. Its notoriety had been predictable. Nudes didn’t move, and certainly didn’t come downstairs. The implications were scandalous: nudes in the living room, whatever next!

The year before, the Salon des Indépendants in Paris had rejected the picture not because it was too radical as a work of art but because its title was too provocative. They didn’t want any fuss in the press; they were, by then, trying to establish Cubism as a serious art form. They asked Duchamp to remove the title, but he refused.

The understandable row in the American media, as it happened, proved to be remarkably good-humoured. The American Art News offered a ten-dollar prize for the best poem about the picture, and awarded it to a ditty that ended: ‘You’ve tried to fashion her of broken bits,/ And you’ve worked yourself into seventeen fits;/ The reason you’ve failed to tell you I can,/ It isn’t a lady but only a man.’

There remains a deep ambiguousness about Duchamp’s sexuality. This was most obviously manifested in his female persona, Rrose Selavy, who appeared intermittently from 1920 to 1941, wearing furs and make up. But it also appeared in his art. His female nudes are masculine and mechanical. It was this coldness in Duchamp that Elsa caught in the portrait she painted of him on celluloid. It is now lost but was remembered by the artist George Biddle: she depicted him as an electric light bulb spitting icicles.

This contrasts with Elsa’s own bracing and embracing personality. She inspired all who came into contact with her, from Frank Wedekind to Ezra Pound, Djuna Barnes and Ernest Hemingway. The photographer Berenice Abbott said ‘The Baroness was like Jesus Christ and Shakespeare all rolled into one… perhaps she was the most influential person to me in my early life.’ Elsa became famous in literary circles from 1918 to 1921 when The Little Review presented her poetry side by side with excerpts from James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Visual art was vitally important to Elsa, but hardly any survives. George Biddle described a visit to her studio in October 1917: ‘odd bits of ironware, automobile tiles… ash cans, every conceivable horror, which to her tortured yet highly sensitive perception, became objects of formal beauty… it had to me quite as much authenticity as, for instance, Brancusi’s studio in Paris.’

Irene Gammel, with immaculate scholarly precision, draws together the threads of the circumstantial evidence surrounding the submission of the urinal to the Independents exhibition in 1917 and comes to the conclusion that Duchamp’s mysterious ‘female friend’ was the Baroness. As Elsa’s, the urinal becomes meaningful. Gammel relates it to several incidents in her life, including her father’s comment that saying one’s prayers was the same as taking a piss before bed. The urinal sent to the Independents exhibition, which was essentially a gentleman’s club, was another sally in her mother’s war against her abusive husband. But it was a much richer image than that.

The urinal, amazingly, was one of a pair, one of the very few sculptures by Elsa to survive. This was a U-bend plumbing trap turned upside down and mounted on a carpenter’s mitre block (therefore framing it, by punning implication, in religion). It looked like a metal ‘g’ and Elsa called it God.

God in one of Elsa’s poems is described as being ‘densely slow – He has eternity backing him’. If god is everywhere, as many believers maintain, he has to be in the most despised corners – in a U-bend to catch blocking waste that could have once been plumbed into a urinal.

Elsa’s sculpture God, however, could also be a portrait of Duchamp. She wrote ‘m’ars [Duchamp] came to this country – protected – by fame – to use his plumbing features – mechanical comforts – He merely amused himself. But I am m’ars tuetonic… I have not yet attained his heights. I have to fight.’ If God is Duchamp, a bent pipe, then the urinal could be a self-portrait. Laid on its back, it takes the form of a womb cradled in a pelvic girdle that could have received Duchamp’s sperm.

America’s declaration of war on Elsa’s beloved Germany on Good Friday 6th April 1917 could have been the trigger that made the spontaneous Elsa submit the urinal, as a late entry, to the Independents exhibition in New York. It would normally have taken three hours to send by train from Philadelphia, where she was living at that time, but the Easter weekend meant that the urinal didn’t arrive at the Independents until Monday, 12 days after submissions had closed.

Elsa didn’t title the urinal but signed it R. Mutt in a script close to the one she sometimes used for her poems, but which is unrelated to Duchamp’s handwriting. R. Mutt, Gammel explains, is a pun on Urmutter, the German Earth Mother whom Elsa’s symbolist friends had adulated in Munich in 1900. R. Mutt could also have been a pun on armut, meaning poverty, Elsa’s own material poverty and the poverty of American culture, which she frequently railed against. And Elsa’s favourite expletive was shitmutt. Everything fitted. The urinal was Elsa’s declaration of war against war, praise for her motherland, and her challenge to the privileged, aloof, sexually ambivalent Duchamp.

The only evidence that survives of the original urinal is the photograph Alfred Stieglitz took of it for Arensberg’s Blind Man 2 magazine. He lit it carefully so that the shadow within the urinal forms the profile of a pristine white, veiled Madonna – Elsa’s and his own German motherland is being fired at. Even more pointedly, as Glyn Thompson has pointed out, Stieglitz chose to photograph the urinal against the American Modernist Marsden Hartley’s painting Warriors, which was not hanging in his gallery at the time but had to be taken out of the storeroom. Warriors was Hartley’s hymn to the German military manhood. Stieglitz, an American German Jew, by photographing them together, identified the urinal with pro-German feeling as America went to war. Stieglitz did not take photographs casually. This suggests that he knew who had submitted the urinal and what it meant.

Gammel, bamboozled as so many have been by the towering status of Duchamp, does not go so far as to suggest that the urinal was solely Elsa’s, but meekly proposes that she ‘was involved in the conception’ of it. The implication is that Duchamp took the final step and made the actual submission to the exhibition. But it was in fact submitted from the address of Louise Norton, the wife of the poet Allen Norton, who knew Elsa well. Duchamp’s name wasn’t linked to the urinal until 1935, when André Breton tried to recruit him into the ranks of the Surrealists.

Any lingering doubt that the urinal could be in whole or even in part by Duchamp has been removed by Glyn Thompson’s examination of what Duchamp was actually doing at that time. Duchamp stopped painting after 1912 and became a follower of the wealthy, indulgent, chess-playing writer Raymond Roussel who built absurd verbal fantasies on words that happened to sound alike but had different meanings.

By 1917 Duchamp wasn’t interested in provoking a debate about art; he was trying to do without visual art. His Readymades made use of ordinary, found objects that had no aesthetic value. They were elaborate, private rebuses, to be read, in a Rousselian way, not seen. None of them were exhibited in galleries because they weren’t works of art. The fact that Duchamp called Elsa’s urinal a ‘sculpture’ in his letter to his sister proves that the urinal couldn’t have been his. Sculpture by then was anathema to him.

Duchamp, on his own admission, didn’t do the urinal. That is proven. Why then did he claim later that it was his? He was, in part, taking his revenge on art. Both his elder brothers, Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp Villon, were successful artists, whereas he was not. Envy and self-loathing seep out of many of his unguarded utterances: ‘why should artists’ egos be allowed to overflow and poison the atmosphere?’ he said in 1963. ‘Can’t you just smell the stench in the air?’

He also appropriated the urinal for practical reasons: he had so little of his own to show. When he eventually gave up trying to be a chess champion in 1933 (his serious ambition till then) it dawned on him that he could build an artistic career by repackaging his early notoriety in America. The problem he faced was that few of his early paintings survived and his Readymades were not visual art, and most of them, anyway, no longer existed, having been allowed to slip back into the visual anonymity from which they had come. Nevertheless, he managed, especially after gaining American citizenship in 1955, to turn himself into one of the grandfathers of modern art, as great as Picasso, Matisse and Mondrian, even though the ‘iconic masterpiece’ he built his reputation on was stolen property.

Tomkins’ upholding of the Duchamp myth has to be considered in the light of MoMA’s support in republishing his ‘updated’ book. The art world as a whole sustains the orthodox view that the urinal is by Duchamp. Countless curatorial and academic reputations and the whole school of Conceptual Art have been founded on this attribution. And national pride is at stake: the urinal was America’s contribution to the founding of Modernism. The date 1917 adds authority, for the urinal is contemporary with Dada and Surrealism.

Added to that is the money. Millions of pounds have been invested in the copies Duchamp commissioned of Elsa’s urinal (there are thought to be 14 of these though the number is disputed), the majority of which are now in public galleries around the world from Paris to Tokyo, London to San Francisco, Ottawa to Jerusalem. It is a sad reflection of our culture that artists can become billionaires by creating collectable objects, whereas poets, even if they make as great a contribution to society, rarely earn more than pennies. Elsa died destitute; she was frequently arrested for shoplifting. In prison she learnt how to make pets of rats.

Duchamp’s urinals need to be relabeled Elsa’s. This could have a profound impact on the future of art. Duchamp’s pinched urinal is nasty, empty and spiteful. His belated explanation of ‘R. Mutt’ as a reference to the J.L. Mott Iron Works (where no-one could have bought this particular urinal) and to the popular newspaper comic strip

Mutt and Jeff is a meaningless obfuscation. Elsa’s original urinal is fulsome, loving and furious. Its form is disquietingly beautiful and its punning signature painfully profound.

That one object can mean two such different things is the chief drawback of Conceptualism. What you see in a found object is not totally orchestrated by the artist, as it is, say, when you look at a Goya, a Matisse or a Michelangelo. Conceptual art is dressed, in part, by the viewer’s own thoughts.

Duchamp made this point in a lecture he gave in Houston in 1957: ‘The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator… adds his contribution.’ And then he added, ‘This becomes even more obvious when posterity rehabilitates forgotten artists.’ He was describing what he himself was doing at that time: faking his own reputation by stealing Elsa’s work and changing what it meant. Conceptual art started then, when he began to build this lie, not earlier, as the orthodox view maintains, in 1917.

Egalitarians in art, Tomkins among them, have argued that participation is liberating for the public because it enables them to contribute to the artistic process. This might be true of minor manifestations of art, like country dancing, but not many feel the need to add their pennyworth to a creation by Rembrandt, Shakespeare or Beethoven.

Spectator contributions are, moreover, subject to deception and self-deception. The naked Emperor was dressed not only in the minds of his beholders but also in his own. Conceptual Art carries such wishful thinking to extremes: it argues that anything can be art if an artist says it is, and that no one has the right to say that something isn’t art nor that someone isn’t an artist. Conceptualism strips art of aesthetic judgment, which is essential to all creative expression. This politically correct philosophy of ‘anything goes’ has to led to the art world being awash with the detritus of found objects, tracks left by would-be shaman, while the disciplined skill of visual creativity, above all the arts of painting and sculpture, have been marginalised.

When Duchamp stole Elsa’s urinal and robbed it of its meaning he was attacking the whole of visual art. Tomkins repeatedly quotes Duchamp as saying that he wanted to put art ‘once again at the service of the mind.’ Since the time of Courbet, Duchamp argued, art had become exclusively ‘retinal,’ in that its appeal was primarily to the eye. This is nonsensical. The retina can’t see. The mind sees. All art is a mental perception, and, in that way, conceptual. To imply, as Duchamp so often did, that the marks of Van Gogh, Picasso, and, later, Pollock were mindless gestures hid his secret loathing of visual art itself.

Elsa’s urinal is the opposite; it is a glorious celebration of visual art. It declares that even the most unlikely, despised object can become, in the hands of an artist, a beautiful, resonant work of art. Elsa’s urinal wasn’t an idea ‘chosen’ by the mind; it was ‘seen’ in an inspired moment of revelation. As such, it re-affirms the primacy of sight in visual art. It deserves to rank alongside Dali’s Lobster Telephone, Picasso’s Head of a Bull made of a bicycle saddle and handlebars and Niki de St Phalle’s target, I Shot Daddy (to which it is similar in feeling).

The back cover of this new edition of Tomkins’ biography is emblazoned with a quote from the critic Richard Dorment: ‘What Tomkins makes us see more clearly than ever before is that Duchamp set art free. By making it more intelligent, he made it more interesting and also more fun. What he did cannot be undone.’ It has to be because he didn’t do it. What he did do has led future generations into making increasingly tedious, repetitious piss-takes of art. Duchamp’s theft is a canker in the heart of visual creativity.

Duchamp – A Biography by Calvin Tompkins. New and Revised Edition. MoMA 2014. 539 pp. £16.95

Baroness Elsa – Gender, Dada and everyday Modernity, a Cultural Biography by Irene Gammel. MIT 2002 534 pp £36.29

Other Articles referred to in this review:

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain: Its History and Aesthetics in the Context of 1917 by William Camfield (in Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century. eds. Kuenzli and Naumann, The M.I.T. Press, 1996)

Marcel Duchamp: A readymade case for collecting objects of our cultural heritage along with works of art, by Rhonda Roland Shearer. Tout-fait. vol. 1 / issue 3. December 2000.

Jemandem ein R Mutt’s zeugnis ausstellen, Monsieur Goldfinch, by Glyn Thompson, Wild Pansy Press, 2008.

¶¶¶

“Did Marcel Duchamp steal Elsa’s urinal?”

Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson

The Art Newspaper, 1 November 2014

The founding object of conceptualism was probably “by a German baroness”, but this debate is rarely aired

Evidence that Marcel Duchamp may have stolen his most famous work, Fountain, from a woman poet has been in the public domain for many years. But the art world as a whole—museums, academia and the market—has persistently refused to acknowledge this fact. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York is the latest eminent body to bury its head in the sand. It has just published a new edition of Calvin Tomkins’s 1996 life of Duchamp, updated by its author. Ann Temkin, MoMA’s chief curator of painting and sculpture, praises Tomkins in her introduction for his “thorough research”. But Tomkins avoids addressing the implications of the question marks over the origins of the work that Duchamp himself raised in 1917.

The public has a right to believe what it reads on a museum label. The Moderna Museet, Stockholm, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Tate Modern, the National Gallery of Canada, the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, the Centre Pompidou, Paris and the Israel Museum should all re-label their copies of Fountain as “a replica, appropriated by Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), of an original by Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927)”.

The extraordinary fact that has emerged from the painstaking studies of William Camfield, Kirk Varnedoe and Hector Obalk is that Duchamp could not have done what he said he did late in life. Irene Gammel and Glyn Thompson have revealed the truth of his much earlier private account that he did not submit the urinal to the Society of Independent Artists exhibition in New York in 1917. Nevertheless, Duchamp’s late, fictional story is still taught in every class and recited in every book.

[Follow the link below to read the entire article — A C-P]

(2017)

¶¶¶

Enduring Ornament, 1913

Enduring Ornament

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, 1913

Reed Enger, “Enduring Ornament,” in Obelisk Art History,

Published August 03, 2017; last modified October 14, 2022

The year is 1913 and Elsa Endell, kaleidoscopic performance artist and poet is on her way to New York’s city hall for her third marriage, this time to a German Baron named Leopold von Freytag-Loringhoven. En route, Elsa spots a rusted iron ring. To Elsa this street trash was a totem of her marriage to be, and in an act marking a new era in the definition of art—Elsa called this found object an artwork.

To state that artwork didn’t need to be created with your hands, but that found objects could be claimed as art through the force of the artist’s intent was a shockingly radical concept. And as so often happens with new ideas, the newly minted Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was not credited with the shattering of artistic tradition. A year later, Elsa’s close friend Marcel Duchamp showcased Bottle Rack, a found object he claimed as a new category of art, the ‘readymade.’

http://www.arthistoryproject.com/artists/elsa-von-freytag-loringhoven/enduring-ornament/.

Portrait of Duchamp (1919)

¶¶¶

“Les nouvelles fables de Fountain 1917-2017”

Michaël La Chance

En avril 1917, une pièce de céramique est déposée au Grand Central Palace, sur Lexington Avenue, afin d’être exposée au salon de la Société des artistes indépendants de New York. Cet urinoir est enregistré sous le nom de R. Mutt. Malgré les principes de base de la Société, dont l’absence de sélection, quelques membres du comité directeur contestent son statut d’œuvre et l’objet n’est pas exposé le soir du vernissage. On apprend plus tard que R. Mutt serait un pseudo dont le prénom est Richard, que l’œuvre est inti- tulée Fountain, que l’adresse du mystérieux R. Mutt est celle de Louise Norton, une femme de lettres qui dirige Rogue, une revue d’avant-garde. Malgré ce dernier indice, il ne fait pas de doute pour la plupart des gens que l’auteur de cette provocation est nul autre que Marcel Duchamp, l’enfant terrible de la scène de l’art. Pourtant, il faudra attendre plusieurs années avant que celui-ci revendique Fountain et se décide à en produire des copies, l’original ayant disparu quelques jours après le scandale.

En effet, au début des années cinquante, des galeristes se présenteront à la porte de Duchamp avec des urinoirs qu’ils lui demandent de signer. C’est que l’urinoir renversé de 1917, malgré sa disparition, ou plutôt parce qu’il a disparu, est l’une des œuvres les plus controversées du XXe siècle. Cent ans plus tard, il importe de revenir sur les « fables » de Fountain, sur la diversité des hypothèses et des scénarios qui entourent l’auteur (ou les auteur.e.s) de l’œuvre ainsi que sur les circonstances de sa création.

(…)

[Follow the link to read this important article — AC-P]

Ref.: La Chance, M. (2017). Les nouvelles fables de Fountain 1917-2017. Inter, (127), 1–74.

https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/inter/2017-n127-inter03190/86333ac/

Limbswish. c. 1917-1918 Metal spring, curtain tassel, and wire mounted on wood block, Height with base: 21 11/16″ (55.1 cm); base approx. 14 x 7 1/2″ (35.6 x 19.1 cm) Mark Kelman, New York

(2018)

¶¶¶

“The urinal that precipitated modern art”

By Glyn Thompson

How a misattributed sanitary fixture kick-started an artistic movement.

December 5, 2018

Since the role played by plumbing in the history of modern art in America has largely escaped the attention of its critics, it would be no surprise it has also failed to fascinate its plumbers, who consequently might be intrigued to learn that the most influential work of art of the twentieth century was a urinal.

Sent under the pseudonym “R. Mutt” to an exhibition in New York on April 9, 1917 — and rejected because Mutt was not a member of the exhibiting society — this ‘submission’ would be misconstrued as demonstrating that art could be anything that an artist said it was, resulting in the colonization by “conceptual art” of galleries from Memphis, Egypt, to Memphis, Tennessee.

This allegedly radical gesture — one that overturned traditional art making — was then misattributed 18 years later to one Marcel Duchamp (1883-1968), but no evidence existed then or now to suggest or confirm that Duchamp had, in fact, been responsible.

In 1982, contemporary evidence from Duchamp’s own hand unexpectedly surfaced and disqualified him. This letter, sent to his sister in Paris, stated plainly that not he but a female friend had sent the urinal to exhibition.

But, secure in the delusion the letter that could expose him had apparently disappeared, in 1966 Duchamp would claim that he had obtained the urinal from the J. L. Mott Iron Works at Fifth Avenue and 17th Street in Manhattan — which would have been impossible, for the following reasons.

First, the Mott catalogue from April 1917 didn’t include the rejected urinal, photographed by Alfred Stieglitz in 1917, and from 1908 all J. L. Mott publicity reiterated that all the plumbing fixtures that it sold it manufactured itself — and this one it didn’t.

Second, vitreous porcelain urinals could be obtained from a manufacturer only by plumbing supply houses, which sold to contractors and master plumbers — not avant-garde artists.

Third, the seven floors of the J. L. Mott building at 118-120 Fifth Avenue (see Figure 2) that were accessible to the public consisted entirely of showrooms from which, as with automobiles, no direct retail purchases could be made, since their exclusive function then, as now, was to display — and many showroom fixtures were under pressure.

And, finally, the urinal in question had actually been made by the Trenton Potteries Company (TPCo) of Trenton, New Jersey, and manufactured in its particular size between 1915 and 1920, but in a smaller size range from 1892 to 1922. This was the Vitreous China Flat-back Lipped “Bedfordshire” No. 2 (See Figure 3) — by 1917, “Bedfordshire” urinals had for decades been made in three almost universally standard sizes.

As the master plumbers of America will be aware, the “Bedfordshire” was the most basic, simplest and cheapest of wall-hung earthenware urinals, the first examples made on and of American soil — copies of English imports — being manufactured by Thomas Maddock in Trenton in 1873 (see Figure 4).

There was, in fact, a “Bedfordshire” model in the Mott inventory (of seven urinals) in 1917 (see Figure 5), but it cannot be confused with the TPCo example since the two clearly differed in critical details.

First, the unique combination and style of perforated ventilator and integral strainer of the Trenton Potteries’ “Bedfordshire” cannot be mistaken for that of the Mott, nor of any other design or make of urinal. And second, the Mott model incorporated a patent overflow that the Trenton Potteries model clearly lacked.

While the system whereby urinals were manufactured, marketed and distributed in the U.S. in the period running up to and beyond World War 1 invalidated Duchamp’s claim, it simultaneously made it easy for his female friend to stroll into any of the scores of high-street plumbers’ shops in Philadelphia — where she resided and from where the rejected urinal would be sent to New York — and pick up a urinal cheaply, for the article in question had suffered a fault in its burning that rendered it useless to a plumber.

This is revealed if an actual example of the urinal (see Figure 7) is compared with another photograph taken of the same article in the summer of 1918, showing it hanging from the ceiling of Duchamp’s studio.

But the fault can only be identified by those who know what they’re looking at, which means that to unravel this conundrum you need to consult Joe the Plumber, who can tell you that the fault had occurred at the dynamic fulcrum of the pattern where the perforated ventilator and the integral strainer meet at the seam joining the back of the urinal to the bowl — rather than a Duchamp ‘expert,’ who can’t.

Mutt’s urinal’s actual author was not exactly a “nobody,” though. On the run from the NYPD for shoplifting, cross-dressing quick-change artist Baroness Elsa Von Freytag-Loringhoven had fled to Philadelphia from New York in January 1917. Astonishingly, the daughter-in-law of the German Kaiser’s Chief of Staff lived precariously on the fringes of the art world, scratching a living as a model, shoplifter and possibly prostitute.

But because she was a woman, she would be written out of the boys’ club of modern art. And since she died in 1927 in relative obscurity (see Figure 8), she wasn’t around in 1935 when her urinal was misattributed by Andre Breton to Duchamp.

Breton failed to cite any evidence in support of his claim. No surprise there, because none exists.

https://www.pmmag.com/articles/101751-the-urinal-that-precipitated-modern-art

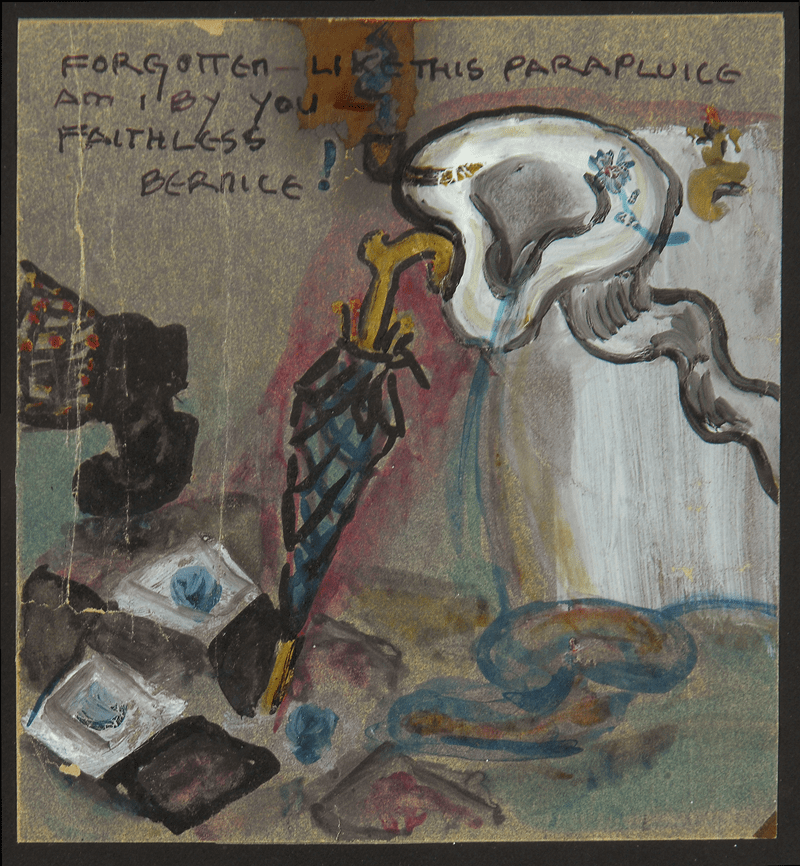

Forgotten—like this parapluice am I by you—faithless Bernice! (1923-1924)

gouache on paper, 13 x 12 cm

© Private Collection

¶¶¶

“The iconic Fountain (1917) is not created by Marcel Duchamp”

Door Theo Paijmans | june, 2018

In 1917, when the United States was about to enter the First World War and women in the United Kingdom had just earned their right to vote, a different matter occupied the sentiments of the small, modernist art scene in New York. It had organised an exhibit where anyone could show his or her art against a small fee, but someone had sent in a urinal for display. This was against even the most avant-garde taste of the organisers of the exhibit. The urinal, sent in anonymously, without title and only signed with the enigmatic ‘R. Mutt’, quickly vanished from view. Only one photo of the urinal remains.

BUT THEN THINGS TOOK A TURN

In 1982 a letter written by Duchamp came to light. Dated 11 April 1917, it was written just a few days after that fateful exhibit. It contains one sentence that should have sent shockwaves through the world of modern art: it reveals the true creator behind Fountain – but it was not Duchamp. Instead he wrote that a female friend using a male alias had sent it in for the New York exhibition. Suddenly a few other things began to make sense. Over time Duchamp had told two different stories of how he had created Fountain, but both turned out to be untrue. An art historian who knew Duchamp admitted that he had never asked him about Fountain, he had published a standard-work on Fountain nevertheless. The place from where Fountain was sent raised more questions. That place was Philadelphia, but Duchamp had been living in New York.

FEMALE FRIEND

Who was living in Philadelphia? Who was this ‘female friend’ that had sent the urinal using a pseudonym that Duchamp mentions? That woman was, as Duchamp wrote, the future. Art history knows her as Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. She was a brilliant pioneering New York dada artist, and Duchamp knew her well. This glaring truth has been known for some time in the art world, but each time it has to be acknowledged, it is met with indifference and silence.

This article addresses the true authorship of Fountain from the perspective of the latest evidence, collected by several experts. The opinions they voice offer their latest insights. Their accumulation of evidence strengthens the case to its final conclusion. To attribute Fountain to a woman and not a man has obvious, far-reaching consequences: the history of modern art has to be rewritten. Modern art did not start with a patriarch, but with a matriarch. What power structure in the world of modern art prohibits this truth to become more widely known and generally accepted? Ultimately this is one of the larger questions looming behind the authorship of Fountain. It sheds light on the place and role of the female artist in the world of modern art.

FORGOTTEN AND IGNORED

Why did Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven never claim Fountain as her work? She never had the chance. While she lived the urinal was thrown out, became lost and quickly forgotten. She died in 1927, eight years before Bréton attributed Fountain to Duchamp for the first time. Decades after her death Duchamp began to commission the first replica of Fountain. While he rose to superstardom, she ended as a footnote in the history of modern art. Her artist career is exemplary for what has happened to countless other female artists who were ignored, marginalized and ostracized from the canon.

In this larger frame, the true story about who really created Fountain’s is one poignant example out of many. It is time for art history to be rewritten – and that time is now.

‘ONE OF MY GIRLFRIENDS’

When Andre Bréton attributes the work to Duchamp in 1935, he remains silent. In the 1960s, Duchamp puts stories into the world that are supposed to confirm that it was his work – stories that are easy to unmask, as it turns out. In the 1980s, a letter from Marcel Duchamp from 1917, in the same month that the exhibition took place, surfaces. In this letter he writes to his sister Suzanne that one of his girlfriends has submitted a urinal for the exhibition. However, this letter does little for the recognition of the real maker. Duchamp has already become the father of conceptual art. He is too big to fail , thanks to ‘his’ masterpiece Fountain in 1917. There are exactly seventeen replicas of Fountainin circulation – in the collections of, among others, Tate Modern in London, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto – all commissioned by Duchamp. None of the replicas mention the name of the real maker: Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

FINALLY

The debate is not over yet. There are pros and cons. But, leaving Fountain‘s authorship aside, it is remarkable that so many people have been able to become acquainted with the genius artist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. As Joyce Roodnat described so beautifully in the NRC last week:

I’m following the debate on the issue. I notice how holy Duchamp is and I think: don’t worry so much. Fountain exists, that’s the main thing. What touches me more is that I only now know about the influential German artist who shook up the New York avant-garde between 1913 and 1923, using her body as an instrument and her life as a work of art in progress. I buy her biography (by Irene Gammel, 2003) and enjoy myself blankly. What a wonderful woman. Pure dada. How is it possible that she is so little known? Why all those exhibitions about Marcel Duchamp and not about her?

Long live Elsa! And all those other great artists that we will discover.

(2019)

¶¶¶

“A woman in the men’s room: when will the art world recognise the real artist behind Duchamp’s Fountain?”

Siri Hustvedt

The Guardian, Fri 29 Mar 2019 13.00 GMT

Last modified on Wed 3 Apr 2019 15.11 BST

Evidence suggests the famous urinal Fountain, attributed to Marcel Duchamp, was actually created by Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Why haven’t we heard of her, asks Siri Hustvedt

The story goes like this: Marcel Duchamp, brilliant inventor of the “ready-made” and “anti-retinal art”, submitted Fountain, a urinal signed R Mutt, to the American Society of Independent Artists in 1917. The piece was rejected. Duchamp, a member of the board, resigned. Alfred Stieglitz photographed it. The thing vanished, but conceptual art was born. In 2004 it was voted the most influential modern artwork of all time.

But what if the person behind the urinal was not Duchamp, but the German-born poet and artist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927)? She appears in my most recent novel, Memories of the Future, as an insurrectionist inspiration for my narrator. One reviewer of the novel described the baroness as “a marginal figure in art history who was a raucous ‘proto-punk’ poet from whom Duchamp allegedly stole the concept for his urinal”. It is true that she was part of the Dada movement, published in the Little Review with Ezra Pound, Djuna Barnes, TS Eliot, Mina Loy and James Joyce and has been marginalised in art history, but the case made in my book, derived from scholarly sources enumerated in the acknowledgements, is not that Duchamp “allegedly stole the concept for his urinal” from Von Freytag-Loringhoven, but rather that she was the one who found the object, inscribed it with the name R Mutt, and that this “seminal” artwork rightly belongs to her.

In the novel, I quote a 1917 letter Duchamp wrote to his sister, Susanne. I took the translation directly from Irene Gammel’s excellent biography of Von Freytag-Loringhoven, Baroness Elsa: “One of my female friends who had adopted the masculine pseudonym Richard Mutt sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.” I got it wrong. Glyn Thompson, an art scholar and indefatigable champion of the baroness as the brain behind the urinal, pointed out to me that Duchamp wrote “avait envoyé” not “m’a envoyé” – “sent in”, not “sent me”. R Mutt was identified as an artist living in Philadelphia, which is where she was living at the time. In 1935 André Breton attributed the urinal to Duchamp, but it wasn’t until 1950, long after the baroness had died and four years after Stieglitz’s death, that Duchamp began to take credit for the piece and authorise replicas.

Duchamp said he had purchased the urinal from JL Mott Ironworks Company, adapting Mutt from Mott, but the company did not manufacture the model in the photograph, so his story cannot be true. Von Freytag-Loringhoven loved dogs. She paraded her mutts on the sidewalks of Greenwich Village. She collected pipes and spouts and drains. She relished scatological jokes and made frequent references to plumbing in her poems: “Iron – my soul – cast iron!” “Marcel Dushit”. She poked fun at William Carlos Williams by calling him WC. She created God, a plumbing trap as artwork, once attributed to Morton Schamberg, now to both of them. Gammel notes in her book that R Mutt sounds like Armut, the word for poverty in German, and when the name is reversed it reads Mutter – mother. The baroness’s devout mother died of uterine cancer. She was convinced her mother died because her tyrannical father failed to treat his venereal disease. (The uterine character of the upside-down urinal has long been noted.) And the handwriting on the urinal matches the handwriting Von Freytag-Loringhoven used for her poems.

All this and more appears in Gammel’s biography. All this and more reappears in my novel. All the evidence has been painstakingly reiterated in numerous articles and, as part of the Edinburgh festival fringe, Glyn Thompson and Julian Spalding, a former director of Glasgow Museums, mounted the 2015 exhibition A Lady’s Not a Gent’s, which presented the factual and circumstantial evidence for reattribution of the urinal to Von Freytag-Loringhoven.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/mar/29/marcel-duchamp-fountain-women-art-history

‘—on n’a que: pour femelle la pissotière et on en vit’

(‘for female there is only the pissoir and one lives by it)

—in La Boîte de 1914 (?)

¶¶¶

Atlas Press

“Marcel Duchamp was not a thief”

This is the first of three pages on this site devoted to the accusation by Professor Irene Gammel, and then by Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson, that the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was involved in the creation of “Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp — indeed, according to Spalding and Thompson, that he actually stole it from her.

Following letters from Dawn Ades in The Guardian and from Alastair Brotchie in The Times Literary Supplement, objecting to repetitions of this unproved allegation, we decided to join forces to refute it factually. By chance, it was around this time that we discovered that Bradley Bailey had found important new information that he was about to publish in The Burlington Magazine (161, October 2019). The same issue therefore included our detailed summary of the factual evidence to date (and this version of it has been updated to include Bailey’s discoveries) and it was hoped that this text would launch a debate between all protagonists based around facts rather than suppositions.

This summary remains the most detailed survey of the facts, along with critiques of the alternative accounts based on these facts.

Here are the complete contents of the pages that follow:

PAGE 1: MARCEL DUCHAMP WAS NOT A THIEF https://atlaspress.co.uk/marcel-duchamp-was-not-a-thief/

Texts 1. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie, “Marcel Duchamp Was Not a Thief”, The Burlington Magazine, December 2019, (an overall summary of the controversy, below).

PAGE 2: MARCEL DUCHAMP AND THE BARONESS https://atlaspress.co.uk/marcel-duchamp-and-the-baroness/

Texts 3. Letters to The Art Newspaper, 320, February, 2020.

3a. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie, “Did Duchamp really steal Elsa’s urinal?”

3b. Julian Spalding, “It’s the world’s first great feminist, anti-war artwork”.

3c. Glyn Thompson, “No grounds for Ades’s view”.

3d. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. Replies to 3b and 3c.

Texts 4. Letter to The Art Newspaper, 322, April 2020. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie, “Urinal row rages on”.

PAGE 3: DUCHAMP AND THE BARONESS: END OF THE FOUNTAIN AFFAIR

Texts 2: Emails from Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie to Irene Gammel.

2a. Email of 26/11/19.

2b. Email to 9/12/19.

2c. Letter of 6/1/20.

2d. Email of 23/1/20.

Texts 5. Irene Gammel. “Last word on the art historical mystery of R. Mutt’s Fountain?”, The Art Newspaper, 326, September 2020.

Texts 6. Letter to The Art Newspaper, 326, September 2020, and expanded response.

6a. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. “The last word? Not likely…”

6b. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. More detailed response to Irene Gammel (Text 5)

Texts 7. Irene Gammel. “Plumbing fixtures: The vexing and perplexing case of R. Mutt’s ‘Fountain’” in The Burlington Magazine, January 2021.

Texts 8. Letter to The Burlington Magazine, January 2021, and expanded response.

8a. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. “The Authorship of ‘Fountain’”, (reply to 7).

8b. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. More detailed response to Irene Gammel (Text 7).

Texts 9. Letters to The Burlington Magazine, April 2021, and expanded response.

9a. Julian Spalding. “‘Fountain’, Marcel Duchamp and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven” (reply to Gammel, text7).

9b. Glyn Thompson. “‘Fountain’, Marcel Duchamp and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven” (reply to Gammel, text 7).

9c. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. “End of the Fountain controversy”, reply to Spalding & Thompson, 9a and 9b.)

9d. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. More detailed response to 9a and 9b.

We leave it to readers to decide if Gammel and Spalding and Thompson have answered our challenge to their different allegations.

Text 1: The Burlington Magazine, December 2019 (with subsequent small modifications)

“Marcel Duchamp Was Not a Thief”

by DAWN ADES and ALASTAIR BROTCHIE

Notes are at the end. This article is being updated (our thanks for corrections from Francis Naumann) in order to make it the definitive account of this affair. The reader will see, as the correspondence unfolds, that neither Irene Gammel, Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson, nor David Lee, editor of The Jackdaw (who expressed his agreement with Spalding and Thompson when he published them), have responded to any of the specific points in this account that dispute their versions.

In November 2014 The Art Newspaper published an article by Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson, ‘Did Marcel Duchamp steal Elsa’s urinal?’1 Their contention, and that of Irene Gammel, the biographer of the artist and poet Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, is that the Baroness was responsible for submitting the famous Fountain, an upturned urinal signed ‘R. Mutt’, to the Society of Independent Artists (SIA) exhibition in New York in April 1917.

The idea of Duchamp as an ‘art-thief’ has become something of an internet meme – accepted as true, without anyone ever bothering to check the evidence. Refuting it then becomes a matter of proving a negative, which is much harder to do. We are well aware that facts and evidence can be rather less amusing than speculation and conspiracy theories, but there is a truth to be revealed here that relates to the integrity of one of the most important artists of the last century, and an artwork frequently judged the most important of the last 100 years. This truth has been carefully obscured by a blizzard of irrelevant research by Spalding and Thompson, the intention of which appears to have been to conceal the fact that no serious evidence whatsoever has been presented that links the Baroness to Fountain. Moreover, Bradley Bailey’s article in The Burlington Magazine published evidence that finally put paid to their speculative contentions. These contentions nonetheless need to be dealt with, and following Bailey’s article we wanted to summarise the facts of this affair.

There are three versions of the events that gave rise to this ‘sculpture’: firstly, the generally accepted account, based on what Duchamp himself said, and accounts by eye-witnesses, the perpetrators and contemporary publications; secondly, Gammel’s speculations in her biography of the Baroness; and thirdly, Spalding’s and Thompson’s account, which attempts to claim Fountain for the Baroness while avoiding the inaccuracies in Gammel’s version.

According to Duchamp’s biographer,2 the idea for the urinal was due to a last-minute impulse. Following a lunch together, and just before the SIA exhibition was about to open, Duchamp, accompanied by Walter Arensberg and Joseph Stella, bought a urinal at a store, and he either took it to his studio or directly to the exhibition venue, signed it ‘R. Mutt’ and attached a submission label bearing the address of Louise Norton. It was then submitted for exhibition, but never was exhibited. Instead it was taken to Alfred Stieglitz’s studio so he could photograph it.3 Duchamp used the inevitable scandal (which would have occurred whether the exhibit was accepted or not) and Stieglitz’s photograph to explain the rationale behind readymades in the magazine The Blindman, again anonymously, through an article by his friend Beatrice Wood.4 Thus two of Duchamp’s female friends collaborated in this affair: Norton and Wood.